The OAT procedure involves the harvest of osteochondral plugs from lesser weight-bearing areas of the knee joint, such as the medial and lateral trochlear ridge and the intercondylar notch. The harvest and placement of the cylinders can be performed arthroscopically, but is often facilitated by a small mini-arthrotomy. Current recommendations limit this technique to the treatment of defects less than 2–3 cm2 in size; larger defects would require harvesting of a significant number of plugs, thus increasing the risk of donor site morbidity. The harvested plugs, generally 6–10 mm in diameter and 10–15 mm in length, are press-fit into the corresponding recipient site (see Figure 2). The donor site is left empty and will gradually fill with bone and fibrocartilage over time. Patients remain on protected weight bearing precautions for approximately four to six weeks with free range of motion. Athletic activities are delayed until four to six months post-op to allow for return of quadriceps strength and proprioception.

Marrow-stimulation techniques such as microfracture and subchondral drilling are arthroscopic procedures that aim to stimulate a reparative response by establishing access for bone marrow elements to the cartilage defect. The defect is cleared of any degenerated tissue, then multiple holes are created in the subchondral bone that allow blood from the marrow cavity to collect in the defect, bringing mesenchymal stem cells that induce a fibrocartilaginous repair tissue (see Figure 3). Patients remain touch-down weight bearing for six to eight weeks and utilize a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine for six hours per day for six weeks. The passive motion is thought to stimulate the generation of a higher-quality repair tissue.

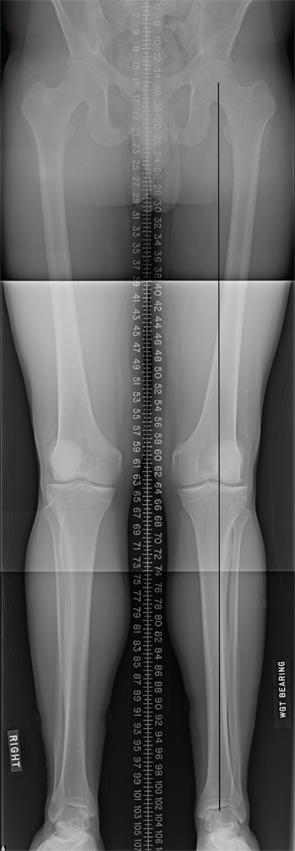

Early attempts at cartilage repair tended to focus on the defect itself, often disregarding articular comorbidities, such as malalignment or meniscal deficiency that were the root cause for the development of cartilage damage in the first place. Not surprisingly, early reports of cartilage repair were disappointing.

Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) is currently the only cell-based therapy for cartilage repair available in the U.S., and is indicated for larger defects in the knee joint (>2–3cm2). It is a two-stage technique that requires the harvesting of a small (200–300mg) cartilage biopsy during an initial arthroscopy. The chondrocytes are released from the extracellular matrix and grown over several population doublings for approximately six weeks. This process is usually interrupted by a cryopreservation phase of up to two years to accommodate insurance approval and scheduling of the secondary reconstructive procedure. For the subsequent implantation, the defect is approached through an arthrotomy and cleared of all degenerated tissue. Originally, a thin layer of periosteum was harvested from the proximal tibia and then sutured as a patch over the defect. The use of periosteum has been largely abandoned due to the high rate at which hypertrophy occurred, which then had to be debrided with subsequent arthroscopy. Currently, the majority of ACI procedures worldwide are being performed with a collagen patch instead.36,37 Once the patch has been secured to the surrounding cartilage shoulders, the suture line is waterproofed with fibrin glue and the chondrocyte suspension is injected into the defect. The cells attach to the subchondral bone and produce matrix to form a hyaline-like tissue that slowly matures over the course of one to two years. Postoperatively, patients are generally kept on touch-down weight-bearing precautions for approximately six to eight weeks while using a CPM machine. Return to high-impact and athletic activities is usually delayed for one year.