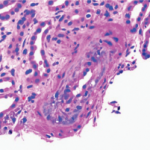

How does one study rare events in uncommon diseases? At a meeting of the Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium a few years ago, a heated debate broke out about the role of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors as prophylaxis for scleroderma renal crisis (SRC). Severe, uncontrolled hypertension and rapidly progressive renal failure characterize this syndrome. The onset of hypertension is abrupt and may be associated with retinal hemorrhages, retinal infarcts, and papilledema. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia is common. The histologic picture in the kidney includes fibrinoid necrosis of the afferent arterioles (see Figure 1, p. 27), intimal proliferation, and/or collagen deposition in the interlobular and arcuate arteries of the kidney.1 Similar findings have been observed in normotensive scleroderma patients with normal renal function.

Before the 1980s, over 80% of SRC patients did not survive. The use of ACE inhibitors has drastically changed these figures. Nevertheless, the prognosis is still not good. Survival at one and five years is only 76% and 65%, respectively, for SRC patients treated with ACE inhibitors. Among SRC patients, 38% never require dialysis, 23% require temporary (2–18 months) dialysis, 19% require permanent dialysis, and 19% die within three months of diagnosis of SRC.2

Because of the relative lack of toxicity of ACE inhibitors and the severity of SRC, it seemed obvious that a trial of prophylaxis would be a good idea. However, recent data on patients with SRC suggest that those on ACE inhibitors at the onset of SRC may have worse outcomes than those not taking these drugs.3 One possible reason is that those on ACE inhibitors may have normotensive SRC and that diagnosis of the crisis may therefore be delayed in these patients. There was concern that a trial of ACE inhibitors may, indeed, carry some substantial risk for participating patients.

Before going ahead with such a trial, my colleagues and I thought that it would be useful to know what the outcome of SRC is in patients who are on ACE inhibitors at the time of onset of the crisis, versus those not on these drugs. However, to find enough SRC patients in any particular clinic—or even in a database—would be very difficult. The prevalence of scleroderma is only about 250 cases per million people and the incidence is only about 20 per million people per year. The latter statistic is important because renal crisis tends to occur only in relatively recent onset diffuse disease. Virginia Steen, MD, of Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., found that between 1972 and 1982, 60 (10%) of 596 progressive systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients developed SRC. The mean interval to SRC after the onset of scleroderma was 3.2 years in that retrospective study.3

Technology as a Tool for Safety Research

Our question was, Could the Internet help us perform this study? Many of us have probably already participated in studies using the Internet. Who has not received a set of questions on SurveyMonkey or a similar questionnaire program? John “Jack” Cush, MD, of Baylor Research Institute in Dallas, has performed several surveys using the ACR’s e-mail list, and he has used Internet technology to study various issues such as rheumatologists’ impressions of the use of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Many of us have also participated in Delphi exercises to obtain experts consensus opinions. However, my colleague Marie Hudson, MD, a rheumatologist at the Jewish General Hospital and assistant professor of Medicine at McGill University, both in Montreal, realized that the Internet could be used as a unique resource for the study of SRC, a rare complication of an uncommon disease.