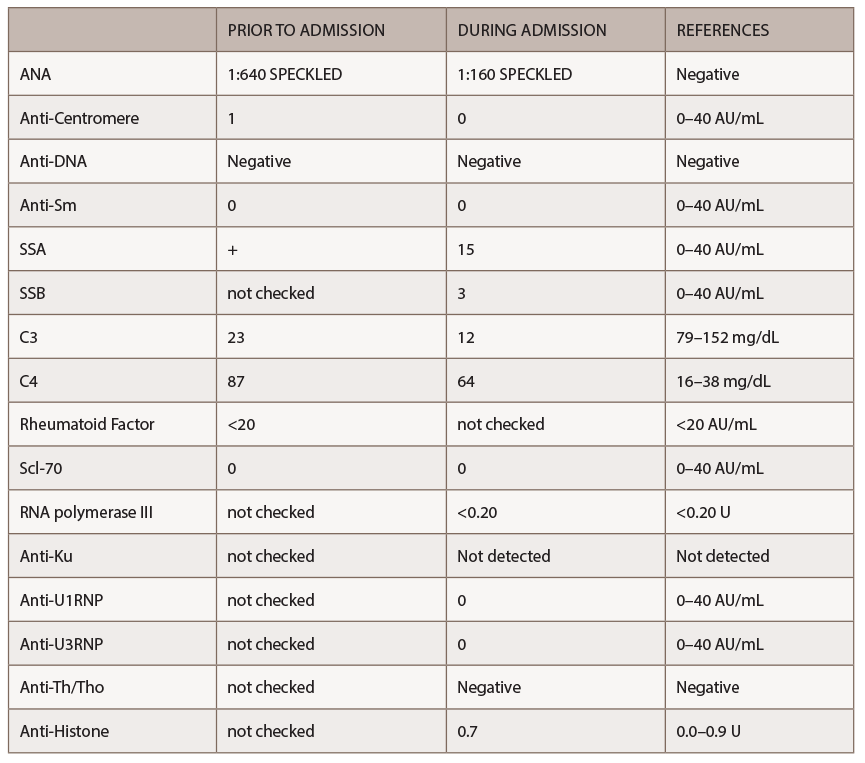

A new battery of autoimmune tests (see Table 2) was obtained and showed only positive ANA (1:160 speckled). Anti-Scl70, anticentromere, anti-RNA polymerase III, anti-Th/To and anti-U1RNP were all negative. This time, SSA, SSB, anti-Sm and anti-dsDNA antibodies were negative. Complement levels were within normal limits. A CT of the chest demonstrated nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) and small bilateral pleural effusions.

Based on the clinical exam findings—specifically, the extensive skin thickening of the face, chest, and upper and lower extremities—the rheumatology team noted this patient satisfied the 2012 ACR classification criteria for definite diagnosis of diffuse systemic sclerosis. Because of the patient’s recent exposure to high-dose steroids and rapid deterioration of renal function, despite a normal blood pressure, the rheumatology consult service suspected SRC.

Per the consulting nephrologist’s request, a kidney biopsy was performed. Renal pathology demonstrated onion skin proliferation within the walls of the intrarenal arteries and arterioles, fibrinoid necrosis and glomerular shrinkage.

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SRC was made. Plasma exchange was stopped, and captopril was initiated. After captopril was started, the patient’s serum creatinine started to stabilize at a value of 3.3 mg/dL.

Twelve months after initiation of treatment, the patient’s kidney function recovered completely, allowing the patient to avoid hemodialysis. She was placed on mycophenolic acid for her skin involvement and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). The patient’s skin thickening has regressed, and now involves only the wrists and calves, with improvement in her respiratory symptoms.

Discussion

Scleroderma renal crisis is a dreaded complication of systemic sclerosis. Usually, SRC is characterized by new-onset hypertension, acute severe renal failure and, in some cases, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia in combination with thrombocytopenia.

The three main risk factors recognized for SRC are skin involvement with a score of more than 10 based on ACR criteria, prednisone exposure at doses higher than 20 mg/day or prolonged use of lower doses, and the presence of anti RNA polymerase III antibodies.3,4

In most cases, hypertension in SRC is defined as a blood pressure above 150/90 mmHg or an increase in blood pressure of 10–20 mmHg above baseline. Cases described in a 2012 study from Guillevin et al. indicated 14% of patients with SRC presented without hypertension.5

Renal failure in SRC is defined as a drop in eGFR of at least 30% or elevation of creatinine 50% above baseline. A renal biopsy can be helpful, but is not required for the diagnosis of SRC, especially if there is a high suspicion and a response to therapy. Renal biopsy may be beneficial, however, in cases in which the diagnosis is inconclusive or evidence of multiple processes exists. In such cases, therapy should be initiated empirically, because a delay in treatment is associated with a poor prognosis.

Hematologic manifestations of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia can occur, but the pathogenesis of these findings remains unclear.

The mainstay of treatment of SRC is angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I). ACE-I should be started and continued even if creatinine levels continue to rise or the patient’s blood pressure has normalized. There is no role of prophylactic ACE-I therapy for prevention of SRC because it paradoxically seems to increase the patient’s risk for developing SRC. Unfortunately, 40–66% of patients never recover renal function, and some will require chronic dialysis. Median recovery time is one year; it is, therefore, prudent to delay evaluation for renal transplantation. Van den Born et al. reported that a modified Rodnan skin score >20, cardiac involvement and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia are all associated with a poor prognosis in these patients.1

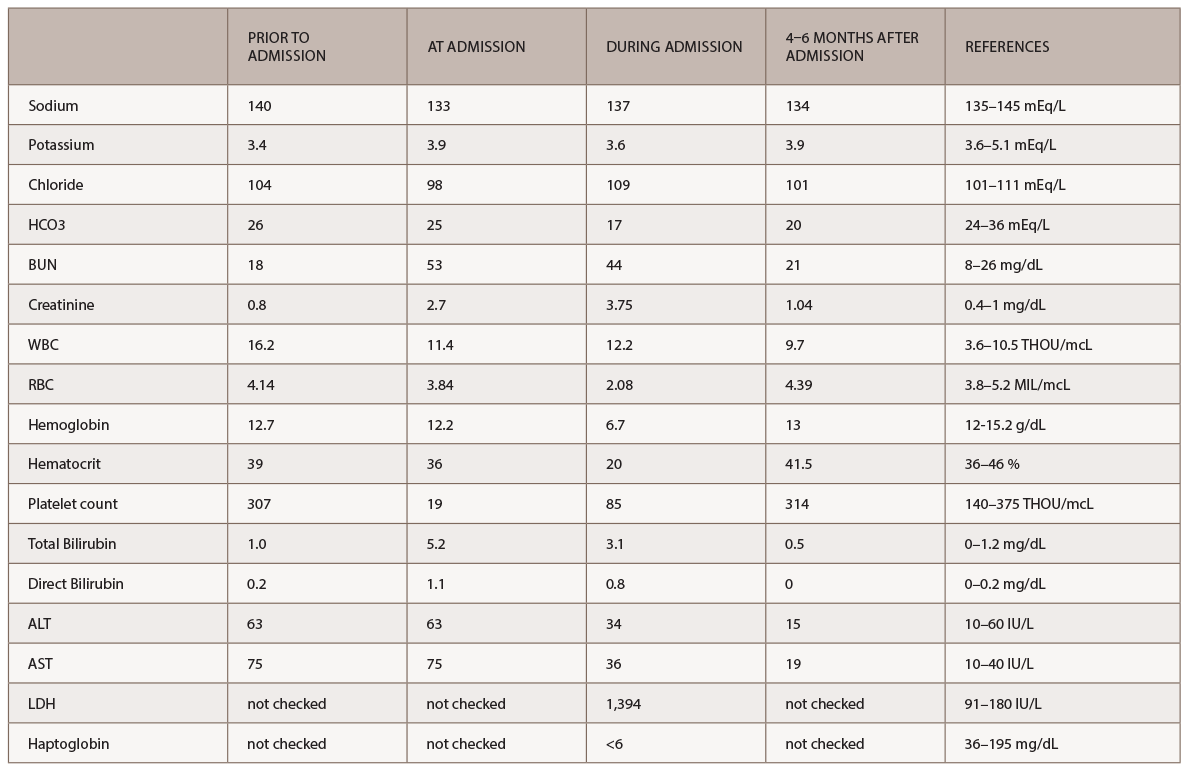

Our patient was treated with as much as 60 mg of prednisone daily for approximately two months prior to presentation due to a misdiagnosis of seronegative inflammatory arthritis. The patient had no underlying history of hypertension or systemic sclerosis. Three months before admission to our hospital, the patient had a baseline creatinine of 0.8 mg/dL and a normal glomerular filtration rate. The acute onset of renal failure at the time of her admission led the primary team to consider atypical TTP and ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis in their initial differential diagnosis. ANCA antibodies were negative, which argued against an ANCA-associated vasculitis.

The rheumatology team, based on the patient’s recent history, clinical exam and autoantibody profile, diagnosed this patient with diffuse systemic sclerosis and suspected SRC immediately. The diagnosis was unusual given the patient’s prior good health and her age at the time of diagnosis. Further, anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies were absent.

Although initially, the patient was treated empirically for TTP with daily plasma exchanges, the patient’s serum creatinine level continued to rise. After the suspicion of SRC was raised, therapy with captopril was initiated, and fortunately for our patient, her renal function recovered within 12 months.