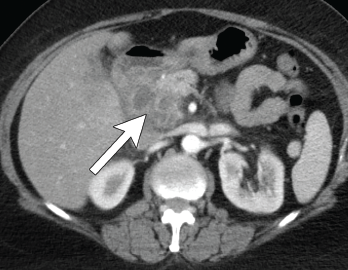

Figure 4. Axial CT showing multilocular abdominal fluid collection.

A 56-year-old woman presented to the hospital with chest and abdominal pain. Her history was notable for pustular psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis (untreated), relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (not on therapy), as well as recurrent abscesses over the preceding four years. Abscesses occurred at the chest wall (see Figures 2 & 3, opposite), axilla and pancreas.

She was treated with systemic antibiotics, although aerobic, anaerobic and AFB cultures were repeatedly negative during each of these episodes. Additional testing included negative results for anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, anti-myeloperoxidase antibody, anti-proteinase 3 antibody and human leukocyte antigen B27. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrated a possible duodenal-colonic fistula that was not further evaluated. Her symptoms improved with corticosteroids.

One year later she was admitted with chest and abdominal pain. She was afebrile, hypertensive up to 200/110 mmHg (RR: <120 mmHg systolic, <80 mmHg diastolic), without tachycardia or abnormal respiratory rate. Initial labs were notable for leukocytosis with a total WBC of 22.2 x 109/L (RR: 4.0–11.0 x 109/L) and elevated inflammatory markers with ESR 82 mm/h (RR: 0–30 mm/hour for women over 50) and a CRP of 10.6 mg/dL (RR: 0–0.6 mg/dL). CT scan of the chest/abdomen/pelvis demonstrated a 2.3×4 cm peri-pancreatic abscess with fat stranding and associated lymphadenopathy (see Figures 4 & 5, p. 22).

Figure 5. Coronal CT showing multilocular abdominal fluid collection.

Cultures from the abscess aspirate again failed to identify an organism, and 40 mg of prednisone daily was initiated. Despite this, she developed a new chest wall abscess over the following days. Incision and drainage were performed, with negative cultures. The following day she developed skin erythema, and pain and warmth at the incision and drainage sites. Due to concern for possible cellulitis, corticosteroids were stopped and she was started on antibiotics.

Ultimately, however, a new chest wall abscess developed, prompting re-initiation of 40 mg of prednisone daily. Her chest wall lesions improved over the following days. Due to suspicion of possible underlying IBD, a fecal calprotectin was tested but proved indeterminate at 106 mg/kg (negative: <50 mg/kg). Colonoscopy was subsequently performed and was unremarkable.

A diagnosis of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis syndrome (SAPHO) was considered given her chest wall lesions and psoriasis, but she lacked other clinical features of osteitis, hyperostosis or acne. She was diagnosed with spondyloarthropathy-associated aseptic abscess syndrome. She was discharged on a prednisone taper and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Aseptic abscesses were first described in 1995 in the case of a 25-year-old man who developed multiple abscesses several years prior to an eventual diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.1 In 2007, the most complete description of this new entity was published with the inclusion of 30 cases from a French registry and 19 cases compiled from a literature review.2 The researchers defined AA by the radiographic appearance of an abscess, negative microbial diagnostic studies, lack of response to antibiotic therapy and rapid response to corticosteroids (see Table 1).2

Table 1: The 5 Features of Aseptic Abscesses

| 1. Presence of abscess on radiologic examination |

|---|

| 2. Histopathology with neutrophilic features |

| 3. Negative blood cultures and infectious evaluation |

| 4. Failure of antibiotic therapy (defined as >2 weeks of therapy or >3 months if concern for tuberculosis) |

| 5. Improvement with steroids |