A 24-year-old woman presented to our rheumatology office in 2017 with a blotchy purple rash on her arms and legs. She reported no history of miscarriage or blood clots.

The rash pattern was concerning for livedo reticularis or livedo racemosa, and she was noted to have an anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:160 with a speckled pattern and an elevated anti-Ro/SSA antibody greater than 8.0; however, antiphospholipid antibodies were not identified. Undifferentiated connective tissue disease was suspected based on her history of Raynaud’s phenomenon, a positive ANA, self-reported fatigue and elevated anti-Ro/SSA antibodies. She was placed on hydroxychloroquine.

She was also noted to have mild leukopenia and was seen by a hematologist, who believed her leukopenia was related to an underlying autoimmune condition.

The patient’s dermatologist biopsied her forehead, with results consistent with rosacea, and a biopsy of her thigh was noted to be supportive of livedo reticularis. At this time, the patient continued to take hydroxychloroquine because she felt it was helping her fatigue.

Over the course of 2018 into 2019, our patient’s livedo worsened, spreading to cover her entire body. Continued serologic monitoring was remarkable for elevated anti-Ro/SSA antibodies and a low-positive ANA. An evaluation for antiphospholipid antibodies remained negative. The test for anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (dsDNA) antibodies was also negative, and her complements were normal.

In May 2019, the patient presented to an emergency department with sudden-onset right upper extremity weakness and numbness. She initially believed the symptoms were caused by a “pinched nerve”; however, when her arm became limp, she went immediately to the local emergency department.

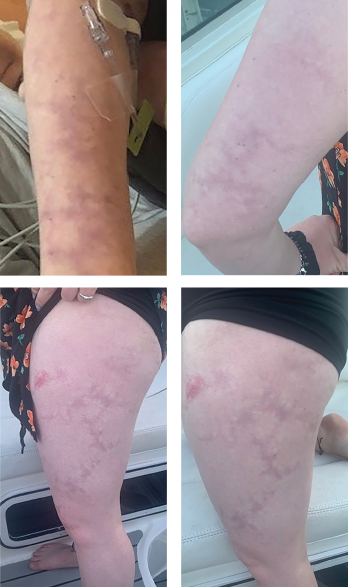

Livedo racemosa, a cutaneous finding characterized by a persistent, erythematous or violaceous discoloration of the skin, in a broken, branched, discontinuous and irregular pattern, is apparent on the patient’s arms and legs.

Upon arrival, the patient was found to have a score of 2 on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated an acute left prefrontal gyrus infarct, with noted additional punctate foci of fluid-attenuated inversion recovery intensity within the cerebral white matter bilaterally.

A computed tomography angiography of her head and neck was nonrevealing, as was a magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of her head. No evidence of stenosis was apparent on an MRA of her neck.

She was administered 325 mg of aspirin, as well as a statin, for stroke prevention by the consulting neurologist.

Transesophageal echocardiography failed to demonstrate a patent foramen ovale or intracardial clot. Laboratory evaluation did not demonstrate evidence of vasculitis or a hypercoagulable state.

After discharge, the patient was initially followed by the neurology practice that she saw in the hospital; she subsequently transitioned care to a neurologist in her home area.

Upon returning home following her stroke, she returned to our practice. The patient’s age, livedo and middle cerebral artery infarct, as well as her nonrevealing workup on repeat antiphospholipid antibody labs and hypercoagulable studies, were concerning for Sneddon syndrome.

Due to the concern for further strokes without a known associated cause, a dermatologist was contacted to perform a repeat skin biopsy, this time with larger margins. The biopsy demonstrated histological findings characteristic of Sneddon syndrome, with obliterative vasculopathy, and changes that included fibrous replacement of medium caliber vascular structures with focal recanalization.

The case was discussed with the patient’s dermatologist, who agreed that based on evidence of a pattern consistent with livedo racemosa (see Figures 1–4, opposite) and characteristic biopsy findings, Sneddon syndrome was a concern.

The patient’s case was discussed with her current hematologist, who agreed that anticoagulation was needed.

The patient has been taking warfarin and continued to have close follow-up with subspecialists. She has not had any further infarcts or events. The patient completed outpatient physical and occupational therapy, but continues to have residual right-hand deficits, including clumsiness, stiffness and loss of fine motor function.