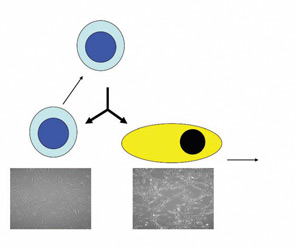

The use of adult stem cells in treatment carries neither ethical nor teratoma complications, but these cells are restricted in their cross-tissue differentiation potential. Although claims of adult stem cell plasticity abound, the number of such transdifferentiation events is too small for a meaningful biological effect. What is emerging, however, is the potential positive paracrine effects of infused adult stem cells such as MSCs on damaged tissue such as myocardium (e.g., postinfarct or inflamed organs, such as acute graft-versus-host disease [GvHD]).

The first use of adult stem cells in clinical medicine was that of hematopoietic stem cells in the treatment of malignant disorders.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Autologous hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) refers to the use of the patient’s own stem cells as a rescue therapy after high-dose myeloablative therapy. In contrast, allogeneic HSCT refers to the use of stem cells from a human leucocyte antigen (HLA)– matched related or unrelated donor. The latter is used for a variety of malignant and nonmalignant disorders to replace a defective host marrow or immune system with the supposedly healthy donor marrow and immune system. More than 10 years ago, the first patients were successfully treated with an autologous HSCT for a life- or organ-threatening autoimmune disease refractory to conventional therapy.1 Table 1 (p. 21) shows the status of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Autoimmune Disease Working Party register as of March 2008.

The goal of using autologous HSCT for the treatment of autoimmune diseases is to reduce or eliminate autoreactive cells, mainly of the adaptive immune system, through conditioning with highly active cytotoxic agents.2 Thereafter, newly developing B and T cells may be introduced to autoantigens and undergo self-tolerization; alternatively, the chance environmental circumstances that led to the initial autoimmunity might never happen again in the patient’s lifetime. The concordance rate of autoimmune diseases in identical twins shows that an autoimmune-prone genetic background alone is insufficient for disease expression. These rates are in the range of 15% for systemic lupus erythematosus to 50% for type 1 diabetes mellitus and suggest that this approach could lead to sustained remissions in some patients. Initially, it was thought that complete ablation of autoreacting cells would be required for durable remissions, but more recent immune reconstitution data suggests that a significant “debulking” of autoaggressive immunocytes could allow the normal immune regulation mechanisms to recontrol the system.3