A rheumatologic disease, most notably primary angiitis of the CNS (PACNS), was another possibility. PACNS has a male predominance, and a mean age of 42 years.4 Clinical manifestations range widely, and include decreased cognition, headache, seizures, and strokes. Normal inflammatory markers, negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and a normal MRA do not exclude this diagnosis. SG had no clear history, clinical, or physical manifestations suggestive of systemic autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet’s disease, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, or polyarteritis nodosa, which can cause CNS disease. In terms of his laboratory tests, his antinuclear antibody (ANA) was negative on initial check and then low-titer positive (1:80) on repeat. Lupus anticoagulant, beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies, and anticardiolipin IgG were negative. Anticardiolipin IgM was in the indeterminate range, and ANCA was negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal and C-reactive protein was very slightly elevated. Standard cerebral angiography was suggested but not performed.

Finally, Susac’s syndrome, or retinocochleocerebral vasculopathy, was considered, given his multifocal MRI findings with involvement of the central fibers of the corpus callosum and leptomeningeal enhancement, in addition to encephalopathy and unilateral hearing loss.5 The finding of branch retinal artery occlusions is central to this diagnosis.

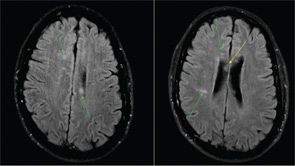

The ophthalmology team was asked to evaluate SG, and a fluorescein angiography of the retina was performed (See Figure 2). A superotemporal branch retinal artery occlusion was seen with focal areas of nonperfusion in the right retina. There were associated areas of perivascular and retinal whitening with cotton wool spots. The occlusion was outside of the macula, which explains the preservation of vision in our patient. Initial imaging of the left retina also revealed an inflamed retinal arteriole; however, the examination could not be completed because of patient noncompliance.

Based on this constellation of clinical and angiographic findings, the diagnosis of Susac’s syndrome was established.

Discussion

Susac’s syndrome, or retinocochleocerebral vasculopathy, was first described in 1979 as a triad of multiple-branch retinal artery occlusions, brain microangiopathy causing encephalopathy, and sensorineural hearing loss.5,6 Since the initial description of this rare syndrome in two young women by John O. Susac, approximately 100 cases have been reported in the medical literature.7 Cases demonstrate a female predominance (3:1) with an age range from 16 to 58 years.6 Susac’s syndrome is described as a “microangiopathy” or a “vasculopathy,” distinct from primary angiitis of the CNS, as only precapillary arterioles are involved.6 Pathogenesis remains unknown, but it is thought to be an immunologically mediated vasculitis of small blood vessels. One case described a microangiopathic syndrome in a patient with features suggestive of systemic lupus erythematosus, although antinuclear antibodies were negative.8 No other links to systemic rheumatologic diseases or to hypercoagulable states have been described. In prior case reports, the encephalopathy, which may be acute or subacute, has manifested with memory loss, dysarthria, ataxic gait, and pronounced psychiatric features, similar to this case.9 Often, patients have headaches, which were not described here. CSF analysis tends to be abnormal with a mild pleocytosis and significantly increased protein level (>100), as was the case with this patient.10