Dr. Kahlenberg

Michelle Kahlenberg, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, says she found the “red flags” particularly “useful to incorporate diagnostic clues on the likelihood of having NMOSD when antibody testing is negative.”

“Given the relapsing nature of NMOSD, you do not want to incorrectly diagnose someone with this disorder if they have another reason for their symptoms,” she says.

(click for larger image)

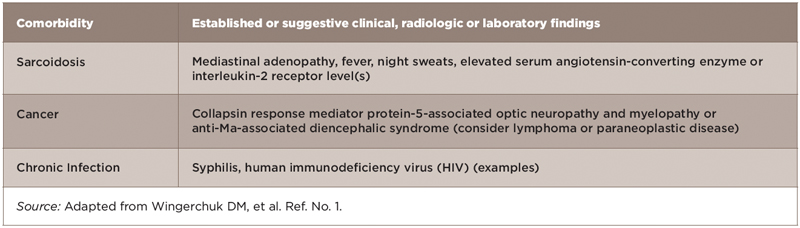

Table 2: Red Flags: Comorbidities Associated with Neurologic Syndromes that Mimic NMOSD

Dr. Kahlenberg also emphasizes that the criteria help facilitate the diagnosis of NMOSD in patients with autoimmune diseases and help tailor the appropriate treatments. “There is occasionally overlap between NMOSD and other autoimmune diseases, and knowing that a patient has NMOSD in addition to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Sjögren’s may change our treatment choices and impacts the prognosis for the patient.”

(click for larger image)

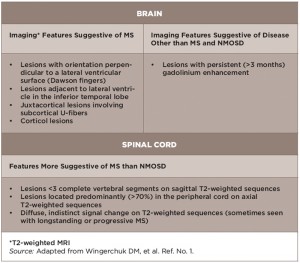

Table 3: Red Flags: Findings Atypical for NMOSD Based on Conventional Neuroimaging

Jason Kolfenbach, MD, assistant professor of medicine and program director of the Rheumatology Fellowship Program, University of Colorado, Denver, also emphasizes that the inclusion of the red flags is particularly helpful to remind clinicians of potential alternative causes of CNS disease, particularly in cases that may not be a classic presentation for NMOSD.

“This is important because clinical symptoms and the underlying etiology that could be identified by the red flags would be treated with potentially much different medications,” he says.

Serologic Testing

The holy grail of NMOSD diagnosis is serologic testing for serum AQP4-IgG. The gold standard, according to Dr. Wingerchuk, is the cell-based assay used by the Mayo Clinic and a few other laboratories. More widely used and accessible is the ELISA technique, which, says Dr. Wingerchuk, has good sensitivity but less than optimal specificity.

Dr. Kahlenberg, who uses the serum test in patients with a clinical suspicion for NMOSD (e.g., MRI lesions or presenting with progressive weakness), says she has not had any issues with insurance coverage for the test and routinely obtains the antibody testing through reference labs.

Dr. Kolfenbach also says that most centers have access to testing either on site or by sending it out to reference laboratories, but emphasizes that cell-based assays are not available at most centers.

Dr. Wingerchuk emphasizes that most commercial laboratories still use the ELISA technique, saying that it is a good technique, but because of its less-than-optimal specificity (compared with the cell-based technique), it can generate false positives. Therefore, he recommends use of the cell-based assay when possible.

Common Scenarios for Rheumatologists

One common scenario that rheumatologists may encounter when seeing a patient with NMOSD, says Dr. Wingerchuk, is a patient with spinal cord inflammation or transverse myelitis. If the patient has multiple sclerosis, MRI lesions would tend to be smaller and shorter in the spinal cord, whereas they would be longitudinally extensive and extend over three or more vertebral segments of the spinal cord in patients with NMOSD. If the latter was found, that would trigger obtaining the antibody test.

The holy grail of NMOSD diagnosis is serologic testing for serum AQP4-IgG. The gold standard, according to Dr. Wingerchuk, is the cell-based assay used by the Mayo Clinic & a few other laboratories.

“In rheumatology practice that would be important because some of these patients who have NMOSD also have some of the rheumatologic antibodies or even rheumatologic diseases, especially lupus or Sjögren’s disease,” he says. “So sometimes when patients have neurologic involvement, it is ascribed to their rheumatologic involvement, when in fact they have coexisting diseases. They have NMO spectrum disorder and lupus, for example.”