Tefi/shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—Celiac disease—the gluten-induced illness that can be seen alongside rheumatic diseases—has been seen much more commonly over the past 20 years than it was previously, but the illness can come with questions that are not always straightforward, an expert said at the ACR’s State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

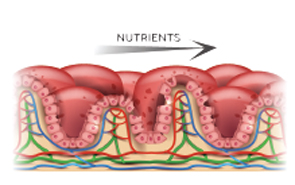

The disease, in which the small intestine becomes inflamed in genetically predisposed people and resolves when they stop eating gluten, used to be thought of as a very rare disorder typically seen in infancy and almost unheard of in North America, said Joseph Murray, MD, professor of gastroenterology at the Mayo Clinic.

The disease now manifests in both adults and children, occurs around the world, shows itself in a variety of ways and is no longer thought to be so rare in the U.S. For example, in Olmsted County, Minn., the county in which the Mayo Clinic is located, the incidence of celiac disease went from close to zero in the 1950s to between 15 and 20 per 100,000 person-years, where it has plateaued for a couple of decades, Dr. Murray said.

“It stayed at a level that’s about 20 times higher than what it was prior,” he said.

According to a study based on data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, about 1.8 million people in the U.S. have celiac disease, although most are undiagnosed and are not on a gluten-free diet, he said. A similar number of people, interestingly, are on a gluten-free diet, but do not have celiac disease.

Dr. Murray

“The irony is, those who have celiac disease are not diagnosed, most of them, even though they would probably benefit from being on a gluten-free diet; whereas, those who are on a gluten-free diet without the diagnosis—it’s uncertain that they even need or benefit from the diet,” Dr. Murray said.

About a quarter of cases present as classic malabsorptive syndrome, with such symptoms as diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss and other problems. About half present as mono-symptomatic, with anemia, diarrhea, lactose intolerance or some other symptom. Another quarter of the patients present with a non-gastrointestinal problem, such as infertility, bone disease, neurological disease, shortness of stature or brittle diabetes.

Rheumatic diseases in which celiac disease is seen include inflammatory myositis, sarcoidosis, juvenile arthritis and primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Some patients also develop a fibromyalgia-like disorder, Dr. Murray said.

A frequent misconception is that a positive HLA finding means that someone has the disease.

Diagnosis

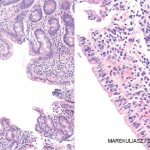

A celiac serology test is used for initial detection and as an adjunct to diagnosis, but the gold standard for diagnosis is villous atrophy, or a flat-appearing pathology, with chronic inflammation, in the proximal small intestine while on a gluten-containing diet.