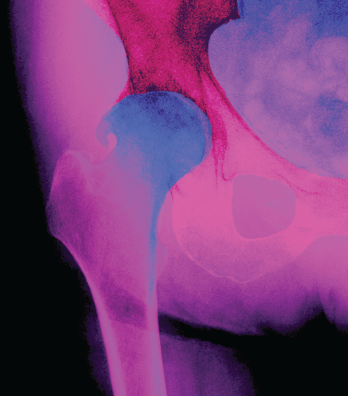

Living Art Enterprises, LLC / science source

CHICAGO—The placebo effect in treating pain in osteoarthritis (OA) should not be discounted, an expert said at the ACR State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium in April.

It’s especially important to accept the effect as real considering that trials of pain therapies in OA generate such high placebo effects (typically at least 40%) and that OA treatment options, especially for prevention of structural progression, remain scarce, with little demonstration of efficacy in platelet-rich plasma therapy, stem cell therapy and prolotherapy, said Joel Block, MD, director of rheumatology at Rush Medical College in Chicago.

Because OA progresses slowly, over decades, studying structural progression in the span of a typical trial is “almost impossible,” Dr. Block said. “Demonstrating an advantage is difficult.” The heterogeneous way in which the disease presents across populations, the confounders seen in the elderly population, the challenges of attrition and how to assess progression are other hurdles, he said.

“That’s why as of today, in 2018, there are absolutely no agents that have been shown to effectively modify the structural progression in humans with OA,” he said.

Drugs originally investigated to slow structural progression, such as hyaluronic acid, have been repurposed for pain and functional improvement, he said. Many have been found to have low effect sizes, but that’s because they’re being compared with placebo, Dr. Block said.

“You might conclude the word placebo is a misnomer when dealing with OA and, maybe, other chronic pain conditions,” he said. “Placebo itself is active treatment by all the criteria we use to define active treatment.” It provides substantial symptomatic relief, has a high effect size and shows durable results, he said.

A formal systematic analysis in 2016 that included 215 OA trials found that, on average, 75% of pain reduction was due to the placebo effect.1

“You need to keep the placebo in mind if you’re going to evaluate new treatments,” Dr. Block said.

Patients will continue to use complementary and alternative medications even after hearing the data clearly show they’re ineffective, he noted. “The reason they do is that they’re actually getting relief,” he said. “That sets up competing imperatives. As a biomedical scientist, it’s my job to demonstrate that an agent is better than placebo, but that assumes the placebo is inactive. When I see patients in the office, it’s quite different. My job is to palliate pain among individuals. I don’t care what the science says, necessarily. Therefore, when I’m evaluating the utility of a novel OA agent, that agent has to be clinically significantly superior to placebo. But as a physician in the office, I just need to make the patient feel better, regardless of how much of that effect is from the placebo.”

‘You need to keep the placebo in mind if you’re going to evaluate new treatments.’ —Dr. Block

Platelet-rich plasma has some evidence suggesting it is effective, but it is not strong evidence, Dr. Block said. “We assume it’s safe, but we also know there’s no compelling reason why anybody would report adverse events,” he said.