5.3 mg/dL before improving rapidly over the next several days to 1.4 mg/dL. Blood pressure was controlled with amlodipine and labetalol. The patient was discharged on prednisone 1 mg/kg/day. Infliximab infusions were resumed at 7 mg/kg every four weeks, and azathioprine was reinstituted at 150 mg/day.

Discussion

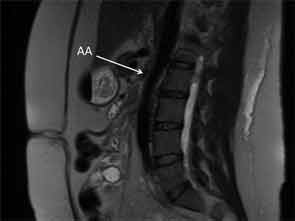

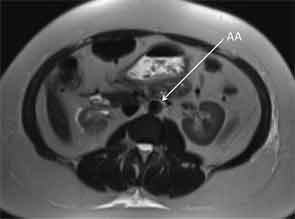

Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) is a well-established but rare form of large-vessel vasculitis. It has also been known as pulseless disease, aortic arch syndrome or occlusive thromboaortopathy. It is a chronic inflammatory arteritis affecting large vessels, predominantly the aorta and its main branches. Inflammation leads to thickening of the arterial wall, resulting in occlusion, stenosis, dilatation and thrombus formation. The vast majority of lesions in TAK are stenotic, but more acute inflammation may destroy the arterial media and lead to aneurysm formation, which is seen in up to one-third of TAK patients.1,2

Published descriptions of this form of arteritis date back to 1830. However, the disease received its name from Mikito Takayasu, a professor of ophthalmology, who in 1905 presented the case of a 21-year-old woman with characteristic fundal arteriovenous anastomoses, which later was suggested to result from retinal ischemia. At disease presentation or during relapses, TAK patients may present with nonspecific inflammatory complaints, such as fever, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, myalgia or arthralgias. This can be associated with vascular pain (e.g., carotidynia). As arterial lesions develop, features like decreased or absent peripheral pulses, vascular bruits, discrepancies in blood pressure between limbs, limb claudication, and hypertension arise. Heart failure can also be seen as a result of aortic regurgitation, longstanding hypertension, or coronary artery disease. Transient ischemic attacks, strokes, mesenteric ischemia, and retinopathy are other manifestations of the resultant ischemia. TAK can affect medium-size vessels, such as coronary arteries, and pulmonary vasculopathy and hypertension are also seen in some patients. Extravascular manifestations that have been reported include dermatologic manifestations, such as erythema nodosum and erythema induratum, glomerular lesions and cardiac manifestations, such as dilated cardiomyopathy and myocarditis.3

Takayasu’s arteritis is most commonly seen in Japan, South East Asia, India and Mexico. It is rare in North America, with an estimated incidence of 2.6 per million per year in Olmsted County, Minn.4 Although geographical differences regarding the distribution of arterial lesions have been described in TAK, the aorta is the most affected artery, followed by the subclavian, common carotid and renal arteries.5 The disease commonly presents in the second or third decade of life and predominantly affects women. From the onset of first symptoms, there is often a delay in diagnosis of months to years.