Dr. Moll also suggested strategies to stratify the risk for the recurrence of DVT or PE. ACCP guidelines recommend three months of anticoagulation for patients who have experienced DVT or PE associated with transient risk factors, such as surgery or major trauma. Patients with unprovoked DVT or PE should receive at least three months of anticoagulation. Those with unprovoked DVT or PE and a strong thrombophilia, such as antiphospholipid antibody (APLA) syndrome, double heterozygosity for factor V Leiden, and the prothrombin 20210 mutation protein C or protein S deficiency, or homozygosity for factor V Leiden, may fall into a higher risk group and may need to be treated with long-term anticoagulation therapy.

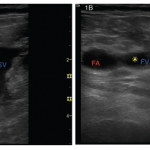

To ascertain the proper length of anticoagulation therapy with warfarin, Dr. Moll would obtain a D-dimer (positivity predicts a higher risk for recurrence; a negative result places the person in the lower risk category) three to six months after the acute DVT or PE and a Doppler ultrasound of the legs (residual thrombus may be a predictor for recurrence). Additionally, Dr. Moll would factor in gender (males have higher risk for recurrence than females), type of thromboembolic event (PEs are more often fatal than DVTs), whether INRs have been stable, any episodes of bleeding, and lifestyle changes. Finally, he includes patient preferences to propose treatment plans and reevaluates the patient’s situation every six to 12 months.

As Dr. Moll and the other panelists noted, thrombosis can occur even with thrombocytopenia. Balancing anticoagulation therapy becomes especially tricky for patients who have APLA syndrome and inflammatory disease. As did Dr. Ortel, Dr. Moll advised the audience that the INR in patients with APLA syndrome can be unreliable and should be correlated with Factor II activity or chromogenic factor X to generate a treatment plan. Learn whether your anticoagulation clinic uses phlebotomy or point-of-care INR testing, he recommended.

Dr. Moll wrapped up his session by touching on the use of contraceptives, specifically the thrombosis risk associated with third-generation pills being greater than that with second-generation pills; vaginal bleeding, for which progestins or endometrial ablative procedures may be helpful; and vitamin K supplementation (100–150 mcg a day) to help stabilize fluctuating INRs. He also recommended two Web sites as good patient-education supplementation: www.stoptheclot.org and www.fvleiden.org.

Treatment Is Empiric

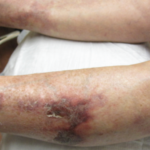

John G. Kelton, MD, a hematologist and dean of the Michael G. DeGroote School of Medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, concluded the symposium with an overview of microangiopathic anemias, especially thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). TTP is still a poorly understood disorder, he noted. Treatment continues to be empiric, based on findings first reported by Rubinstein in 1959 that plasma exchange produced unexpected remission from TTP—an illness that, untreated, has a mortality rate of 90%.3 Dr. Kelton and his colleagues in the Canadian Apheresis Study Group conducted a study 18 years ago of patients with TTP, some of whom had lupus and other autoimmune markers.4 Their study compared plasma infusion with plasma exchange, demonstrating a significant benefit of the latter, which continues to be a mainstay of treatment for these patients. At his institution, clinicians do not use the ADAM TS-13 test as a measure of disease activity. The test, said Dr. Kelton, cannot inform a clinician about altering, stopping, or continuing therapy.