Rheumatologists often have varying levels of comfort in assessing and managing muscle disease. For many, these diseases are challenging because of the difficulty in accurately diagnosing myopathies and establishing effective therapeutic regimens. We outline three key issues in diagnosing and managing inflammatory myopathies.

No Gold Standard for Diagnosis

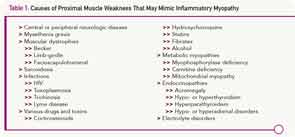

Because there is no gold standard for diagnosing idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, we are forced to rely on criteria. Although more than a dozen sets of criteria have been proposed, the first set, published in 1975 by Bohan and Peter, remains the mainstay.1,2 For the diagnosis of polymyositis, they proposed the combination of proximal muscle weakness, elevated serum levels of enzymes derived from skeletal muscle, a classic triad of electromyographic (EMG) abnormalities, and the presence of inflammation on muscle biopsy. The diagnosis of dermatomyositis could be rendered with the addition of a characteristic skin rash. These parameters seem clear cut until one gets into the details, because each criterion by itself is very nonspecific. For example, fixed proximal muscle weakness may be the hallmark of inflammatory myopathies, but this symptom may be caused by a myriad of other conditions (see Table 1).

When elevated, the enzyme most considered to be a sign of myositis is creatine phosphokinase (CPK). It is sometimes mistakenly believed that CPK must be elevated at least one time during the course of polymyositis, but this is not always the case. Some patients have normal CPK levels throughout their course. Furthermore, there are several other causes of an elevated CPK, including exercise (anaerobic and aerobic), trauma (blunt or sharp), drugs (statins, colchicine, alcohol, cocaine), and toxins. Carriers for muscular dystrophy or some metabolic myopathies may have an increased serum CPK. Healthy African-American males commonly have CPK levels above the upper limits of normal reported for the population as a whole. Finally, in large clinical trials using statin drugs, over 30% of individuals have elevated CPK levels. Interestingly, the percentage was the same for those taking placebo as it was for those taking study drugs.3 Thus, relying on this test as a way to screen for muscle inflammation can be problematic.

The classic triad of EMG changes described includes: 1) fibrillation at rest, increased insertional activity, and spontaneous and positive sharp waves; 2) bizarre high-frequency repetitive discharges; and 3) polyphasic potentials of short duration and low amplitude.1,2 However, this triad is not diagnostic and is generally present in only 40% of patients with myositis, while 10% of patients with these diseases have normal EMG results.4