Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in The Rheumatologist in a two-part series in February and April 2009. The topic and this article remain highly relevant, and Dr. Schur has updated it here.

Laboratory testing is an essential element in the diagnosis and management of patients with rheumatic disease. This article focuses on a diverse array of serological markers that can provide unique information on the status of the patient’s immune system that is important in clinical evaluation as well as scientific inquiry. These tests help in the diagnosis of a particular disease, and importantly, they may help monitor disease activity. Indeed, immunological testing represents one of the bedrocks of rheumatology and is a distinguishing feature of our specialty.

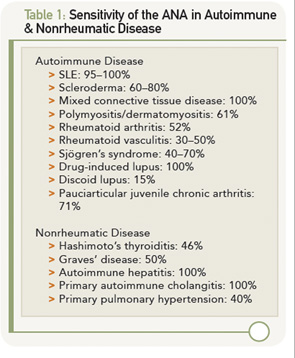

Although there are many available tests, the approach to serology follows the traditional approach of any laboratory study. Critical in the interpretation of any serological test is determining its sensitivity (i.e., that proportion of patients with the target disorder who have a positive test), specificity (i.e., that proportion of patients who are free of the target disorder and have negative or normal test results), and positive and negative predictive values, which calculate the likelihood that disease is present or absent based on test results using the test’s sensitivity, specificity and the probability of disease before the test is performed (pretest probability). This review covers data on antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and tests for rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Antinuclear Antibodies

ANAs are the signature autoantibodies of the rheumatic disease and are tested in many clinical scenarios.1-3 These antibodies are usually detected by immunofluorescent (IF) techniques, utilizing Hep-2 cell lines, and specific antinuclear antibodies are detected by solid-phase immunoassays—for example, an ELISA. One hundred and eighty autoantibodies have been described so far in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).58 The IF ANA is generally screened at a dilution (i.e., titer) of 1:40, and, if positive, serial dilutions are carried out until a dilution is negative. Most labs titer to 1:1280, but some go higher. It is not clear whether titering higher is clinically useful, because the titer of an ANA usually does not correlate with clinical activity.

The IF ANA test is especially useful as an initial screen for patients suspected of having systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). ANA testing is also useful for the evaluation of patients with other suspected rheumatic conditions including Sjögren’s syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), drug-induced lupus erythematosus, dermato-/polymyositis, scleroderma, adult and juvenile arthritis and autoimmune hepatitis. However, the presence of an ANA does not signify the presence of illness, because these antibodies may also be found in otherwise normal individuals. As shown in Table 1 (left), the sensitivity of the ANA for a particular autoimmune disease can vary widely.