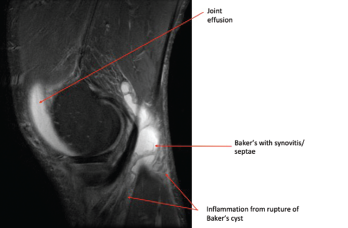

Photo 2: This MRI of the right knee shows a large joint effusion and a ruptured Baker’s cyst with synovitis.

In patients with Lyme arthritis today, synovitis is usually the presenting manifestation of Lyme disease, and a history of suspicious tick bite or classic erythema migrans skin lesion is often lacking. Patients with Lyme arthritis rarely have a history of prior treatment for Lyme disease, because early treatment largely prevents the progression of infection to clinical arthritis. Unlike patients with early Lyme disease, who typically present in the late spring and summer, Lyme arthritis patients may present at any time of the year.

Patients of any age may develop Lyme arthritis, but children are particularly affected, with 35% of cases occurring in 10- to 14-year-olds, and older adults are also increasingly affected.1 Children may have more acute presentations. Adult Lyme arthritis patients generally don’t have the severity of pain that occurs in patients with septic arthritis caused by such bacterial organisms as Staphylococcus aureus.

Affected joints in Lyme arthritis often have large effusions (see photo 3). Baker’s cysts are commonly found. Rupture may occur and be a presenting manifestation, which may mimic deep venous thrombosis with calf swelling and pain. Joints may be warm, but the overlying skin is not usually erythematous. Affected joints may be uncomfortable, and patients may have limited range of motion due to the size of an effusion.

Serum serology, particularly IgG antibody response, is the key diagnostic test for Lyme arthritis. Because Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of untreated Lyme disease, high levels of anti-Borrelial antibodies are present & serology is a highly sensitive test.

In addition, patients with Lyme arthritis usually lack fever or systemic symptoms.

Serum serology, particularly IgG antibody response, is the key diagnostic test for Lyme arthritis. Because Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of untreated Lyme disease, high levels of anti-Borrelial antibodies are present and serology is a highly sensitive test. Serologic testing is currently performed using a two-tier testing strategy, starting with an ELISA test followed by a confirmatory IgM and IgG immunoblot for positive ELISA tests.3 In Lyme arthritis, IgG immunoblots are always positive (with five or more IgG bands). Moreover, a highly expanded immune response is seen, often with 7–10 IgG bands. IgM bands may be present as well, but are not required for the diagnosis, and the presence of an IgM antibody response alone should not be used to confirm the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis.

ESR and CRP levels may be elevated in some patients with Lyme arthritis. Hematologic abnormalities, such as thrombocytopenia or anemia, are atypical and—along with other symptoms, such as fever—could raise concern for other tick-borne co-infections.

Synovial fluid analysis is important to exclude other causes of oligoarthritis, including crystalline disease and other infectious agents. Synovial fluid white cell counts in Lyme arthritis are in the 10,000–25,000 white blood cells/µL range. Culture and gram stain are not available for B. burgdorferi but may be performed to evaluate for typical bacterial pathogens. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for B. burgdorferi DNA is often positive prior to antibiotic treatment and may help confirm the diagnosis.

Serologic testing is not validated for use on synovial fluid, and measurement of Lyme antibody responses in joint fluid is not recommended.

Imaging studies are not required for the evaluation of Lyme arthritis. However, plain films may show effusion. Ultrasound or MRI can be used to evaluate for synovitis and tendinitis, and for diagnosis of Baker’s cysts. Radiographic erosions are rare in Lyme arthritis.