Although lumbar spinal stenosis will have a major effect on public health, the number of studies on appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic choices is surprisingly small. Despite this lack of evidence-based options, clinicians need to make the best choices with available evidence and clinical acumen. In this article, I will provide my approach to this challenging clinical disorder based upon the available medical literature and my experience of 29 years in practice.

Definition and Pathogenesis

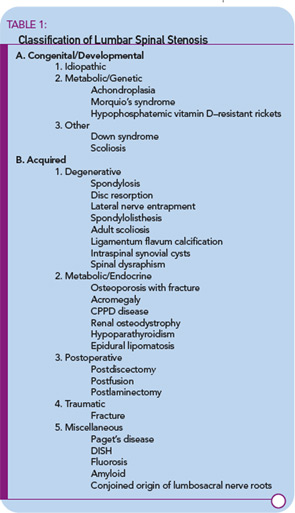

Spinal stenosis is a disorder characterized by insufficient room in the spinal canal for the neural elements. Most commonly, acquired degeneration of the anatomic structures of the lumbar spine results in narrowing of the central spinal canal, the lateral recesses, or the neural foramina. Acquired or secondary stenosis will be the focus of this article. Other major categories of spinal stenosis include other forms of acquired stenosis as well as congenital and developmental disorders.2 (See Table 1)

A basic understanding of the pathogenesis of this disorder is essential for making therapeutic decisions for the corresponding form of spinal stenosis. What might be appropriate for an intervertebral disc herniation (a form of acutely acquired spinal stenosis) will not necessarily be effective for spinal narrowing that has been decades in the making.

The earliest changes occur in the intervertebral discs that lose their structural integrity and start to flatten. The resulting biomechanical insufficiency results in transfer of stresses posteriorly to the ligaments and facet joints. The response to the added weight results in the development of osteophytes on facet joints and vertebral endplates, as well as the redundancy and thickening of the ligamentum flavum.3 Depending on a number of physical factors including the central anterioposterior diameter of the canal, trefoil canal shape, and the height of the neural foramina, stenosis may occur in different areas of the spinal canal with attendant clinical syndromes corresponding to the location of compression. For example, more severe central stenosis may cause urinary retention symptoms. Persistent radicular pain that is unrelieved with a change in position is more indicative of lateral recess stenosis.4

The mechanism of radicular pain production in spinal stenosis is incompletely understood. Individuals with similar degrees of canal narrowing experience different intensities and locations of pain. Mechanical compression of nerve roots may cause electrophysiological alterations in nerve conduction. However, slow, persistent compression is associated with neural adaptation that does not lead to symptoms. Simple compression of the neural elements alone does not fully explain the generation of radicular pain. Vascular compromise associated with arterial, capillary, and venous obstruction plays a substantial role in the development of neurogenic claudication.5 Standing in an extended posture decreases the room in the spinal canal while flexion increases the space.