LOS ANGELES (Reuters)—A new front in the battle over the cost of expensive medicines in the United States is opening up in Oklahoma, the first state where the government’s Medicaid program is negotiating contracts for prescription drugs based on how well they work.

In June, Oklahoma received approval from the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to factor how effective a prescription medicine is into the price it pays to the manufacturer.

The state has signed its first contract under this strategy with Alkermes Plc for injected schizophrenia treatment Aristada (aripiprazole lauroxil), and is close to new agreements for an expensive antibiotic and an epilepsy drug, Nancy Nesser, pharmacy director at the Oklahoma Health Care Authority, told Reuters.

An Alkermes spokesperson said the arrangement is intended to “encourage patients to stay in treatment longer and meet treatment goals.” List prices for the long-acting drug, given every month to six weeks, start at about $1,200 a month. Under the one-year contract, the price decreases every other month as long as the prescription is refilled.

“The longer the member takes it, the better the rebate,” Nesser said.

State-run Medicaid departments are powerful purchasers in the $450 billion U.S. market for prescription medicines. By law, the health program for the poor and disabled receives a mandatory 23 percent discount off drug prices, and often negotiates additional rebates for individual medicines.

But state governments have struggled to keep up with steep drug price increases each year, as well as expensive new medications for diseases including hepatitis C and cancer.

President Donald Trump has promised to lower prescription drug prices, and in May unveiled a “blueprint” with dozens of proposals to deliver on that pledge.

One proposal would allow some state Medicaid departments to exclude certain drugs from reimbursement, a tactic used by private insurers to demand larger discounts and one that would represent a more significant change. But it is not yet clear how states could do so under federal law without losing existing statutory rebates, healthcare experts said.

In the meantime, Oklahoma’s move can give the state more leverage over drugmakers, state officials say.

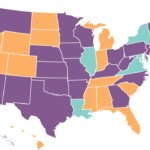

Other states are considering whether to follow Oklahoma’s lead, according to Nesser, who has fielded inquiries from several Medicaid departments.

Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services – which spends nearly $2.4 billion annually on drugs for Medicaid members – told Reuters it will request approval for a program similar to Oklahoma’s, although details are still being worked out.