Physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, resulting in an estimated 3.3 million deaths a year globally, accounting for 6% of global deaths.1,2 A sedentary lifestyle (i.e., too much sitting) is associated with an increased risk for all-cause and chronic disease-related morbidity and mortality, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, various cancers and obesity.3,4 People living with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) will experience several additional benefits from being more physically active, including improved mobility, strength, physical functioning, mood and bone health, as well as reduced fall risk, with little risk of increased pain or joint damage.5,6 However, despite the clear health benefits of a more active lifestyle, people living with RA remain less active than their age- and gender-matched peers.7-9

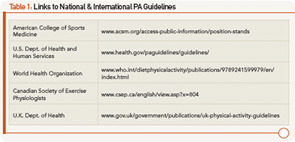

The health promotion message of Exercise More, with the goal of meeting weekly physical activity (PA) guidelines for moderate- or higher-intensity aerobic exercise, is widely adopted.2,10,11 International guidelines recommend that adults aged 19–65 acquire at least 150 minutes (two-and-a-half hours) of moderate-effort aerobic activity each week, accumulated in bouts of at least 10 minutes, to receive health benefits. Guidelines also suggest that similar benefits can be achieved with 75 minutes (one and one-quarter hours) of more vigorous activities, similarly acquired in sessions of 10 minutes or more over a week. Additionally, it is recommended that adults also include strengthening, flexibility and balance-type activities two or three days a week2,10-11 (see Table 1).

The health promotion message of Sit Less is also becoming more widely known.12 Adults in North America spend up to 60% of their waking time (i.e., nine hours or more each day) sitting or lying still.13 Replacing time spent sitting or lying around while awake with activities that involve standing up and moving around a little bit reduce the health risks associated with a sedentary lifestyle.14 Moreover, the health benefits associated with being less sedentary have been shown to be independent of whether or not the same person is also meeting PA guidelines.15

Notably, the specific health benefits associated with reducing sedentary behaviors for people living with RA have not been specifically explored. However, it can be argued that the message of some light activity is better than none may have even more relevance for someone living with RA, whose pain and fatigue can play roles in limiting their ability to participate in higher-intensity activities.16 Additionally, encouraging people living with RA to replace prolonged sitting with light activities fits well with our other health messages around the importance of joint protection, pacing and energy conservation.

What Does “Exercise More” Mean?

Every day, adults living with RA should plan to do two to three moderate-to-vigorous-effort physical activities that they need to do or like to do and can do comfortably for at least 10 minutes. Note:

People living with RA should aim for 20 to 30 minutes of moderate-effort activities every day, done in bouts of 10 minutes or more at a time.

- Moderate effort means the heart rate, breathing and body temperature will increase a little bit with activity, but the person can still talk or carry on a conversation without difficultly. At the end of a moderate-effort activity, a person should feel refreshed. Moderate-effort activities include purposeful walking around 3 mph (>100 steps/minute), standing and intermittent walking activities that require moderate upper-extremity use, such as raking leaves and circuit-based low-resistance training.

- Need to do includes activities that need to be done regularly as part of the normal weekly routine (e.g., walking the dog, vacuuming or gardening) or occupational activities (e.g., walking from the bus stop/car to work, packing boxes for shipping or moving).

- Like to do means working leisure or recreational activities into your weekly plan that are both enjoyable and include an element of socialization (e.g., walking with a friend, attending a pool exercise class, fishing while standing—not sitting).

- Comfortable means there should be no additional joint discomfort or swelling during or immediately after the activity. New activities should be introduced gradually and monitored to ensure there is no increase in disease activity with progressing both the effort and time doing the activity.

- People living with RA do not need to participate in more vigorous activities to achieve the health benefits associated with aerobic physical activity. However, there are many potential physical and emotional health benefits to participating in higher-intensity activity, as long as there is no increase in fatigue or joint symptoms.17 Note the following:

- Vigorous-effort activities generally leave a person tired, sweaty and a little short of breath after a few minutes and include activities that most people traditionally consider exercise, such as jogging, climbing several flights of stairs or using a push mower.

- Participation in vigorous physical activities should be introduced gradually, beginning with a trial session of 10 minutes or less, depending on joint symptoms. This trial should be followed by a day with no vigorous activity to monitor if the new activity is contributing to an increased level of fatigue or acute joint symptoms.

- Balancing the amount of time doing moderate- vs. vigorous-effort activities during any one activity session (e.g., 10 minutes of activity = five minutes of brisk walking [moderate effort] + five minutes of jogging [vigorous effort]) can be a helpful way to self pace and reduce the overall physical stresses to the body and joints while also gaining the additional health benefits from a more physically active lifestyle.

What Does “Sit Less” Mean?

Breaking up sitting time by standing up to stretch and take a few steps every 20–30 minutes will reduce sedentary time by about two minutes.