“There’s a big problem with exposure,” she says.

Though rewarding in other ways, rheumatology pays less than other specialties, which may cause doctors searching for a niche to overlook the field—and the pediatric rheumatology subspecialty—in favor of more lucrative propositions. Pediatric rheumatologists, like their adult counterparts, face additional financial hurdles because insurance fails to reimburse them for tasks that are routine to their practice.

“A lot of what we do, such as talking on the phone about lab results and helping patients and parents interpret new symptoms, is nonreimbursable,” says Dr. von Scheven.

One way to raise the subspecialty’s prominence is to expand training opportunities across the country and spread the word of the unmet need for pediatric rheumatologists now and in the future. New efforts have been launched in recent years with some success.

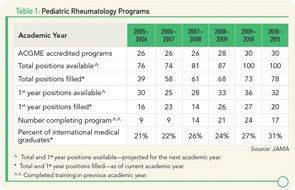

Accredited pediatric rheumatology training programs in the U.S. increased from 26 in 2006 to 30 by 2011, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association (see Table 1). Still, some institutions wanting to add the subspecialty to their programs find it difficult to acquire financing, especially when current fellowship openings go unfilled.

“I anticipate total fellowship training positions would grow if all currently available positions were filled,” says Dr. Henrickson. “Funding fellowship training positions is a challenge for academic institutions. However, there remain fewer applicants than available positions.”

The total number of pediatric rheumatology fellows increased from 74 in 2006 to 93 in 2010 and then dropped to 86 in 2011, according to the ABP, indicating slow and bumpy progress in recruitment. “Those are still teeny, weenie numbers of people graduating and not sufficient to meet the number of people who are retiring,” says Dr. von Scheven.

To get noticed among the competition of other specialties and attract residents with limited exposure to the field, the ACR developed a pediatric residents program to encourage undecided pediatric residents to consider subspecialty training in pediatric rheumatology.

Kids Speak

Sonja Graham’s daughter is 14 years old and sees a pediatric rheumatologist every three months. If her arthritis flares, visits increase to once a month. The Grahams live in Tupelo, Miss., and drive three hours each way to get to appointments. Their state has only one pediatric rheumatologist.

“It puts a huge financial burden on our family,” says Graham. “I have to miss a day of work. Gas money is $100, and if we have to stay at a hotel that’s another hundred.”