“Many people who reject stereotyping and prejudice nonetheless believe in these biological differences,” Ms. Hoffman says, adding that the study suggests these false beliefs could be contributing to racial disparities in pain management and causing harm to patients.

A ‘lack of empathy for black individuals is a proximal cause of pain treatment biases.’ —Dr. Drwecki

A Look at the Data

That racial bias in pain assessment and treatment exists is not a new finding. Several studies show that black patients receive lower quality pain treatment than white patients, including those presenting to the emergency department.2

What is new in the study by Hoffman and colleagues, according to Robert Edwards, PhD, Department of Anesthesiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, is the examination of false beliefs and “the discovery that holders of these false beliefs are more likely to exhibit racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations.”

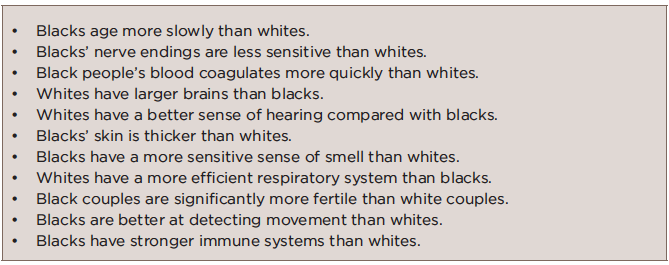

In the second part of the two-part study (the first part looked at beliefs among white laypersons), 222 white medical students and residents were given two case studies (one of a black patient and the other of a white patient) and asked to estimate their pain and make a treatment recommendation. They were then asked to complete a list of beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Table 1 (below) lists the 11 false beliefs reported.

TABLE 1: False Beliefs Held by Participating Medical Students & Residents

Source: Ref. 1, Table 1.

The study found that the white medical students and residents who held these false beliefs about biological differences showed racial bias in their perception and treatment recommendations, and specifically rated the black patients’ pain as lower than white patients’ pain, which resulted in less accurate treatment recommendations for black patients.

Highlighting that most of the white medical students and residents sampled held inaccurate beliefs about fictional differences, Dr. Edwards also points out that they failed to report actual differences supported by the evidence (e.g., a higher risk for heart disease and stroke in blacks compared with whites).

With regard to pain, he says that “it is especially unfortunate that some people seem to assume blacks are less sensitive to pain than whites, because a good deal of research suggests the opposite—that individuals from an ethnic minority background tend to show greater sensitivity to pain and susceptibility to many chronic, disabling pain conditions.”

A Different Shade of Racial Bias?

Among the research showing that black people may actually have enhanced pain sensitivity is a study published in 2014 that found that black patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) displayed increased pain sensitivity to noxious stimuli (e.g., thermal heat, punctuate pressure and cold pressor task) and greater increases in pain when receiving repetitive pulses of heat and pressure (i.e., temporal summation) than white patients.3 These findings held true after adjusting for education and annual income.