Biophoto Associates / Science Source

WASHINGTON, D.C.—Experts speaking at the 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting session, Update on Small-Vessel Vasculitis, offered insight into the latest approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of diseases involving the inflammation of blood vessels.

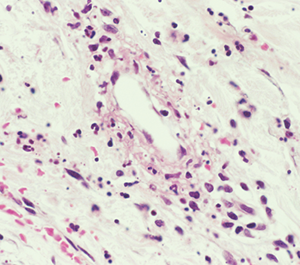

“Vasculitis is an immune-mediated process. White blood cells invade the vessel wall, causing inflammation throughout the vessel wall,” said Jason M. Springer, MD, MS, director of the Vasculitis Clinic at Kansas University Medical Center in Kansas City, Kans. Occlusion of the vessels may affect downflow of blood to tissues, which then necrotize.

Although types of vasculitis are divided by the sizes of vessels involved—small, medium, or large—“this isn’t a perfect system,” Dr. Springer said.1 “There’s a lot of overlap in terms of the sizes of blood vessels involved in these diseases. Some forms of vasculitis don’t follow the rules.” Vasculitis may be either a primary or secondary disease, and rheumatologists must also rule out vasculitis mimics, including antiphospholipid syndrome and atherosclerosis.

Eponyms Are Out

Traditional eponyms for the small-vessel vasculitides are now out of style, said Dr. Springer. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis includes microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly called Wegener’s granulomatosis) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly Churg-Strauss disease). Immune complex vasculitis, in which immunoglobulins and complements form complexes that can deposit in vessel walls, includes cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (CV) and IgA vasculitis (formerly Henoch-Schönlein purpura).

No current diagnostic criteria exist for vasculitis. The Modified ACR Classification Criteria for vasculitides were published in 1990, and do not reflect current diagnostic tests or disease definitions, he said. Classification criteria are meant to identify already-diagnosed patients for clinical trials, not for clinical diagnosis. New diagnostic and classification criteria in vasculitis are now being developed by investigators who presented an early draft of their GPA criteria at the 2016 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. The 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definitions of vasculitides provide one way to distinguish these diseases from others.2

Diagnosis is based on clinical features, biopsy and testing for ANCA antibodies.

“Just because the ANCAs are negative, don’t rule out these types of vasculitides,” said Dr. Springer.

With indirect immunofluorescence, c-ANCA antibodies tend to stain diffusely in the cytoplasm of the neutrophils, and p-ANCA stains around the nucleus. ELISA or EIA assay tests identify enzyme targets within the neutrophils, such as PR3-ANCA or MPO-ANCA. Look for antibody test results that correlate; the majority of GPA patients have a c-ANCA with a PR3-ANCA pattern, and most MPA patients show p-ANCA with MPO-ANCA. Although some patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis have unusual antibody patterns, this may be a sign to look for another diagnosis, Dr. Springer noted.

GPA

GPA is ANCA positive in 80–90% of cases, said Dr. Springer. It is characterized by granulomas and often affects organ combinations, especially the kidneys, lungs and ears, nose and throat (ENT).3 GPA patients may have a bloody, crusting nose and sinusitis that doesn’t respond to antibiotics.