Lyme disease has been a difficult journey.

—Allen Steere MD

In 1975, Polly Murray, an artist residing in the idyllic town of Old Lyme, Conn., was clearly worried about the health of her four young children.1 Recently they had all developed skin rashes and flu-like illnesses. One son, Todd, had been diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and another son, Alex, had developed an unexplained stiff and swollen knee. Murray was not reassured by the pediatrician’s assessment that there was absolutely no link between their illnesses. Nor were her fears allayed by the discovery that twelve children in Lyme had recently been diagnosed with JRA. There were no obvious explanations for this outbreak. Some people speculated that a nearby nuclear power plant was to blame. Others ascribed it to contaminants present in the town’s drinking water supply.

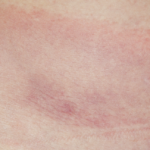

I have heard from reliable sources that Murray contacted several Boston-area teaching hospitals seeking their help, but to no avail. She found a more receptive audience in Connecticut, where an epidemiologist working in the State Department of Health put her in contact with Allen Steere, MD, then a first-year rheumatology fellow at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn. Dr. Steere, whose previous training had been in the field of epidemiology, paid a visit to Lyme, a wooded hamlet of 5,000 residents nestled at the mouth of the Connecticut River. He was intrigued. A preliminary surveillance study of three contiguous towns—Lyme, Old Lyme, and East Haddam—identified 39 children and 12 adults with some form of inflammatory arthritis.2 Most of the patients resided in heavily wooded, sparsely settled areas and there appeared to be a peak occurrence of the illness in the summer months. What might be responsible for this outbreak? The patients’ physical examination findings and laboratory test results did not point to a specific cause. The breakthrough clue came after a meticulous review of the patients’ histories, when Dr. Steere discovered that one-quarter of them had noticed a rash in the shape of a bull’s-eye pattern develop a few weeks before the onset of the arthritis. Olé!

Bull’s Eye

The history of the bull’s-eye rash brings us back to the early years of the twentieth century when a Swedish dermatologist, Dr. Arvid Afzelius, presented a paper to the Dermatologic Society of Stockholm that described a patient with an expanding skin lesion, which he termed erythema migrans. Paradoxically, this rash, which faded within a matter of weeks, was renamed erythema chronicum migrans. A dozen years later, Dr. Afzelius, who studied under the famed Hungarian physician and dermatologist Moritz Kaposi, presented a second report on a series of six patients with this rash:3