Spondylarthritis (SpA) refers to a group of disorders with overlapping clinical features, estimated to affect between 0.5% and 2% of the population.1,2 Most often included in the SpA group are ankylosing spondylitis (AS), which constitutes about half of SpA, reactive arthritis, the arthritides associated with psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease, and undifferentiated SpA. Although the majority of SpA starts in the third or fourth decade of life, a significant proportion of patients (10–20%) begin to experience symptoms during childhood. In pediatric rheumatology clinics, SpA accounts for up to 15–20% of the cases of inflammatory arthritis, with oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, and systemic juvenile arthritis accounting for the majority.

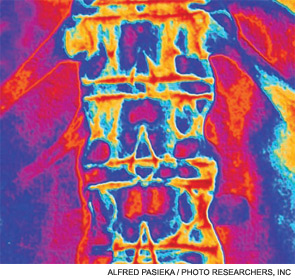

The most severe and often most debilitating form of SpA, AS, involves the axial skeleton and causes inflammation in the sacroiliac joints, vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, and facet joints. Structural remodeling results in pathological bone formation in the form of osteophytes and syndesmophytes. These structures bridge vertebral bodies, leading to reduced spinal mobility and eventual fusion. At its earliest stages, SpA is often undifferentiated (i.e., lacks defining clinical or radiographic features) and may not involve the spine. The lack of axial involvement and related symptoms such as inflammatory back pain is particularly notable in children, who instead have a greater tendency to develop enthesitis and arthritis in the hips and other large joints of the lower extremities.3

Progression from undifferentiated SpA to AS is unpredictable in adults and children, and there is often a long lag period (8–11 years) between the onset of symptoms and a diagnosis of AS.4-6 Prompt recognition and management of early axial SpA, whether presenting in children or adults, is our best hope to alter the disease course and improve long-term outcomes. However, identifying those patients with undifferentiated SpA who are most likely to develop axial disease and AS, as well as appropriate pathways and targets for therapeutic intervention, remain important unmet needs in SpA.

The Classification of SpA

Recognizing SpA in children and distinguishing it from other forms of juvenile arthritis can be a challenge. Rosenberg and Petty recognized the need for specific classification criteria in the early 1980s and proposed the concept of the seronegative enthesopathy and arthropathy (SEA) syndrome. This syndrome has been defined as enthesitis with arthralgia or arthritis in children less than 17 years of age who also lack rheumatoid factor (RF) and antinuclear antibodies.7 The features of the SEA syndrome helped distinguish SpA from juvenile arthritis, classified at the time as juvenile rheumatoid or juvenile chronic arthritis, without relying on evidence of axial involvement.