Beginning January 1, 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)—formerly the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA)—changed the rules eliminating consultation codes.1,2 The code was eliminated with this new policy by CMS and was not vetted through the Carrier Advisory Committee (CAC). According to a letter to CMS dated August 30, 2009, the American Medical Association (AMA) did not agree with this policy and urged CMS to work with the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Editorial Panel to explore alternatives.3

Research and Reactions

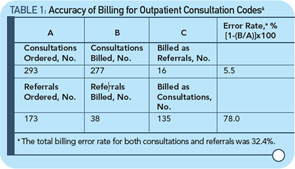

With this background, a recent article by Joel Shalowitz, MD, MBA, professor of health industry management at the Kellogg School of Management of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., defended the elimination of consultant codes.4 The objectives of the Shalowitz article were to describe the reasons for the codes, analyze the accuracy of the codes and project the financial repercussions of the elimination of consultations codes; the article also include recommendations for their continuation. The article involved the review of 500 requests for consultation and concluded that there were actually 293 consultations, 5% which were billed incorrectly; 173 were actually referrals of which 135 (78%) were incorrectly billed as consultations (see Table 1, above). The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) was the reason patient-specific data was excluded from the analysis.4 In this study, there was no attempt to evaluate the quality of the consultations. The financial impact of changing the code was measured by correcting coding for consultation versus new patients codes, and showing how much money could be saved by paying less (see Table 2, below).4 The estimate for savings for Medicare was $534.5 million per year.

Dr. Shalowitz states that payment for services should be equalized, especially since the “consultant physicians are paid so much more than their primary care physicians for the same or less time spent with them.”4 In my opinion, this contention is wrong and Dr. Shalowitz has no data to support its validity. For cognitive consultative physicians, it is frustrating to read that the time spent on their consultations is “the same or less” than that of the primary care physician. I do not believe that this is true in rheumatology consultation.

Because of its designs, the article cannot assess the quality or impact of a consultation; rather, it focuses on coding and costs and not on care. As such, it can encourage the insurance company approach: Our costs will be less if we pay less. Importantly, in my view, the article uses the flawed interpretation of AMA semantics to distinguish between a referral and a consultation. I think that the approach to the patient can be virtually the same. If we call the encounter a new patient, however, we get paid less.