Racial and ethnic quotas are fast becoming distant memories, but for the first half of the 20th century, they represented significant barriers to career development and advancement. During and after World War I, the American Jewry became the target of anti-Semitism from a variety of social groups, including the Ku Klux Klan and various immigration restriction advocates.

Ivy League universities were no exception, and several of these schools moved to restrict Jewish enrollment during the 1920s. Nativism and intolerance peaked in 1922 when the number of Jewish students at Harvard tripled to 21% of the freshman class (up from 7% in 1900). Harvard’s president, A. Lawrence Lowell, proposed a quota on Jewish enrollment, convinced that the university could only survive if the majority of its students came from old American stock. He proposed a 15% maximum number, reasoning that this would actually prevent future anti-Semitism. His suggestion was followed by most Ivy League universities as well as many others throughout the nation.1

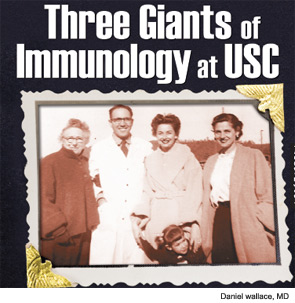

Although 3,000 miles away, the University of Southern California (USC) School of Medicine in Los Angeles was no exception. Founded in 1885, it closed in 1920 due to lack of a sufficient endowment. The school resumed operations in 1928 and graduated its first class in 1932, concurrent with the opening of Los Angeles County General Hospital, which, for several years, was the largest hospital in the United States and had over 3,000 beds. Other than a small Seventh Day Adventist medical school known as College of Medical Evangelists (later Loma Linda), USC was the only medical school in Southern California, because the University of California (UC) Los Angeles, UC San Diego, UC Irvine, and UC Riverside were not built until the 1950s and 1960s. From 1931 until his sudden death weeks before Pearl Harbor, Paul S. McKibben, PhD, was the dean of the USC School of Medicine. He restricted the 54-member class to three members of the Jewish faith and one woman.

Companionship Born of Adversity

The Jewish classmates enrolled in the freshman class of 1940 included Samuel Rapaport, MD (1921–2011), Benjamin Simkin, MD (1920–2003), and my father, Leon Wallace, MD (1920–2009). They were exposed to institutional hazing by classmates, pranks, and insults that were condoned by the administration. As a consequence, the trio of Rapaport, Simkin, and Wallace became very close while carpooling and eating together so that wartime gas and food rations could be stretched.