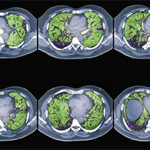

First, assess the distribution of abnormalities. What area of the lung is involved? Are the abnormalities located at the top or bottom (i.e., apical or basilar)? Inner or outer (i.e., central or peripheral)?

Next, describe the dominant pattern of the abnormalities. Look for the following:

- Reticulation: too many fine lines;

- Groundglass: an increase in lung tissue density that doesn’t obscure the vessels;

- Consolidation: an increased density obscures the vessels and air bronchograms may be present;

- Nodules: too many dots;

- Honeycombing: small cystic black spaces touching each other, a sign of end-stage disease;

- Air trapping on expiratory images; and

- Traction bronchiectasis: dilated airways in areas of abnormal lung, another sign of fibrosis.

“Description and distribution may be diagnostic, obviating the need for lung biopsy,” Dr. Guttentag said. “They also help inform therapeutic intervention and prognosis. For example, a patient with honeycombing and traction bronchiectasis has established fibrosis that won’t respond to immunosuppressive therapy. But groundglass and consolidation could indicate active inflammation that’s potentially reversible.”

Most importantly, consider the clinical information. “Do the CT findings support your clinical diagnosis?” Dr. Guttentag asked. “The age and sex of the patient, acuity of symptoms and social and occupational history are all relevant here. And of course, is there clinical evidence of connective tissue disease [CTD]?”

‘Don’t ever order a CT chest with & without contrast unless you’ve spoken to radiology & there’s a good reason for it. It just doubles the radiation dose.’ —Dr. Guttentag

CTD ILD

Generally, CTD presents in the lungs as one of various patterns of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP). Dr. Guttentag said, “Think of IIP as the way the lung is reacting to an insult. These are nonspecific histologic patterns of lung injury. The lung has limited ways of responding and trying to heal, and these insults may be autoimmune, inhalational, infectious, idiopathic or drug induced. The history, clinical exam and serologies are going to help put the pattern in the context of a clinical picture.”

ILD may precede clinical manifestations of CTD by months to years. “Up to 15% of cases of IIP will eventually be diagnosed with CTD, but IIP patterns aren’t specific to one CTD. There’s a lot of overlap,” Dr. Guttentag said.

“For example, many CTDs present with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). It’s ‘nonspecific.’ On the other hand, the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern is most commonly seen in patients with rheumatoid lung. Systemic lupus erythematosus tends to show up with pleural-pericardial disease or hemorrhage. And systemic sclerosis almost always manifests with NSIP. So if the pattern doesn’t fit with what you typically see in that disease, consider whether they have something else superimposed. History, lab data and communication with radiology are critical.”1,2