Along this line, inhibiting the synthesis of adipnectin or its downstream effects would appear to be a promising therapeutic goal.5 The key question is, Does it work? The results on this issue are puzzling. Standard treatment with methotrexate appears to increase adiponectin levels in humans and application of a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor increased adiponectin in an arthritis animal model. Although adiponectin resembles TNF in its tertiary structure, the true effect of TNF inhibitors on adiponectin expression also still needs to be determined.12,13 Interestingly, experimental treatment with anti-TNF antibodies can downregulate adiponectin-dependent stimulation of synovial fibroblasts significantly.9 This finding also raises the question of whether TNF inhibitors are truly specific for TNF (which, if they are not, might even be an advantage for the patients).

Resistin is another powerful adipokine that is synthesized in the lining layer by macrophages, B cells, and plasma cells, all strongly operative in rheumatoid pathophysiology.6,14 Resistin concentrations in synovial fluid have been found to be higher than in plasma and correlated positively with levels of several inflammation markers including C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, IL-1Ra, and TNF-α. Resistin, in turn, is inducible by TNF-α, IL-6, and IL‑1β in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), resulting in a positive feedback mechanism of inflammation. These effects can be reduced by blocking the key transcriptional element NF-κB, leading to the idea that resistin-induced inflammation is NFκB dependent. However, the true potential of this adipokine in the pathogenesis of arthritis is illustrated nicely by the effects of direct injection in joints of arthritis-susceptible mice. In this case, inflammation and joint destruction started immediately and in a rapidly progressive manner. Of note, anti-TNF treatment of RA patients seems to reduce resistin serum levels—as well as CRP—significantly.12

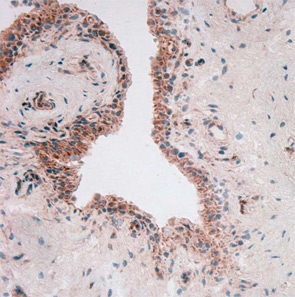

To throw adipose tissue–adipokine restriction dogma further overboard, another adipokine had to be introduced into this challenging scientific game: visfatin/PBEF. Lymphocyte aggregates and vascular endothelial cells predominantly synthesize visfatin in rheumatoid synovium (see Figure 2). Visfatin activates human leukocytes, induces co-stimulatory molecules on the cell surface of monocytes, and induces proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, TNF, and IL-6 in these cells; it also protects fibroblasts and neutrophils from apoptosis.7

Protective Adipokines

One question is frequently asked: Where are the “protective” adipokines? Similar to the proinflammatory cytokines, there should be at least one. So let’s therefore revisit the effects of “protective” leptin. The basis for this positioning is the observation that leptin-deficient ob/ob mice developed a less severe arthritis in comparison with wild-type mice. In humans, levels of leptin are positively correlated with the overall body fat content, but a true correlation between inflammation and leptin plasma concentrations is still under discussion.