Checking blood levels of commonly used disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has gained widespread attention in the rheumatology community, even resulting in a recent guidance document from EULAR for biologics.1 Although a highly useful tool, drug level measurement in rheumatology is not without challenges; many of our drugs violate the basic principles of pharmacology that we learned in medical or nursing school. For example, biologic drugs can have non-linear kinetics; mycophenolate undergoes enterohepatic recirculation; and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is highly variable in drug pharmacokinetics between patients. If this sounds intimidating, don’t worry. This tutorial covers the basics of therapeutic drug monitoring (aka the art of checking drug levels) and provides practical guidance for both clinicians and researchers.

Checking blood levels of commonly used disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has gained widespread attention in the rheumatology community, even resulting in a recent guidance document from EULAR for biologics.1 Although a highly useful tool, drug level measurement in rheumatology is not without challenges; many of our drugs violate the basic principles of pharmacology that we learned in medical or nursing school. For example, biologic drugs can have non-linear kinetics; mycophenolate undergoes enterohepatic recirculation; and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is highly variable in drug pharmacokinetics between patients. If this sounds intimidating, don’t worry. This tutorial covers the basics of therapeutic drug monitoring (aka the art of checking drug levels) and provides practical guidance for both clinicians and researchers.

The Need for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Historically, therapeutic drug monitoring was best used for drugs that had a narrow therapeutic index—that is, drugs for which toxicity could occur with small changes in dosing or individual alterations in drug pharmacokinetics. However, we’ve since learned that pharmacokinetics for our commonly used small molecule and biologic DMARDs vary widely among patients with rheumatic diseases. This wide variability in pharmacokinetics can occur due to a patient’s genetics, which alter drug metabolizing enzymes or drug transporters; the effects of a disease, such as hypoalbuminemia from lupus nephritis or impaired gastric motility from systemic sclerosis; and differences in body composition; among other causes. Practically speaking, there is a growing recognition that no one-size-fits-all approach exists to dosing for DMARDs.

Drug level measurement is one tool that looks downstream from dosage to better relate drug exposure to clinical response, and can be used to individualize a patient’s dosage. Additionally, drug levels can be used to identify medication non-adherence and allow for counseling interventions to improve patient outcomes.2

Although drug level measurements can guide clinical management, the correct interpretation of drug levels requires at least three crucial pieces of information:

- The timing since the last dosage was taken;

- The dosage; and

- The number of doses taken (e.g., adherence, attainment of steady state).

Step-by-Step Guide to Interpreting Drug Levels

Step 1: Timing Is Everything

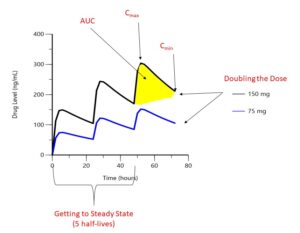

FIGURE 1: Drug levels over time. Hypothetical drug administered orally every 24 hours. (Click to enlarge.)

The first step to interpreting a drug level is finding out when your patient took their most recent dosage. As shown in Figure 1, drug concentrations change significantly between the highest concentrations (Cmax or peak) and its lowest (Cmin or trough). The area under the curve (AUC) represents the total concentration of drug present over a given period of time. For an intravenous (IV) drug, maximum concentrations occur at the end of the IV infusion, whereas for an oral or subcutaneous drug, maximum concentrations occur when the process of absorption equals the process of elimination, which although unique to each drug, is typically hours after the dose is taken for small molecules and days for biologic drugs. Trough concentrations are typically measured at the end of the dosing interval, right before the next dosage is due. When a patient first begins a medication, drug levels will accumulate with each dosage until steady state is reached, which occurs after five drug half-lives; so it is important to know how long your patient has been taking their medication.